An Interview with Isol

Isol

May 30, 2018

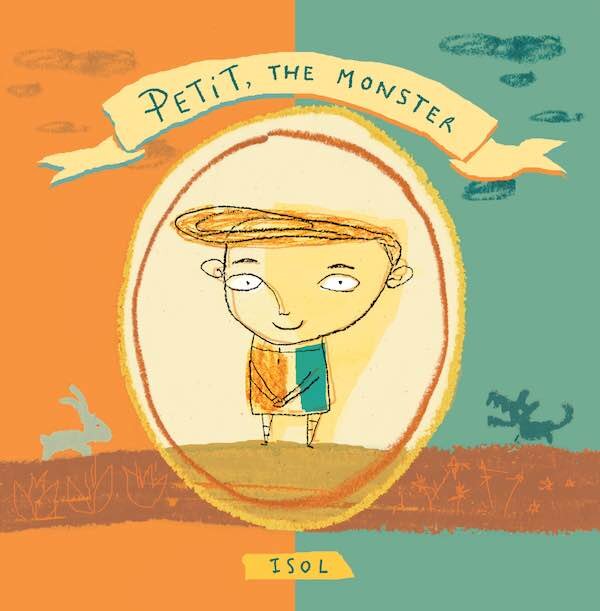

We interviewed Isol (Marisol Misenta), award-winning children's book illustrator and author. Recognized for her free-spirited style, she was the 2013 winner of the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award, one of the most prestigious awards in children's literature. She has written and illustrated eleven books of her own and illustrated works by other authors, including six by Argentinian poet, Jorge Luján. She was also a finalist for the Hans Christian Andersen Award in 2006, 2007 and 2014. Isol lives and works in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

A Selection of Work

In our opinion, this quote from her acceptance speech bears repeating: "I don’t actually think that I must put a limit to my imagination just because it’s a book for children, on the contrary! What reader could be more demanding than a child? Children have a lot of things to discover and I’d better be on their high level in order to satisfy their huge capacity for curiosity."

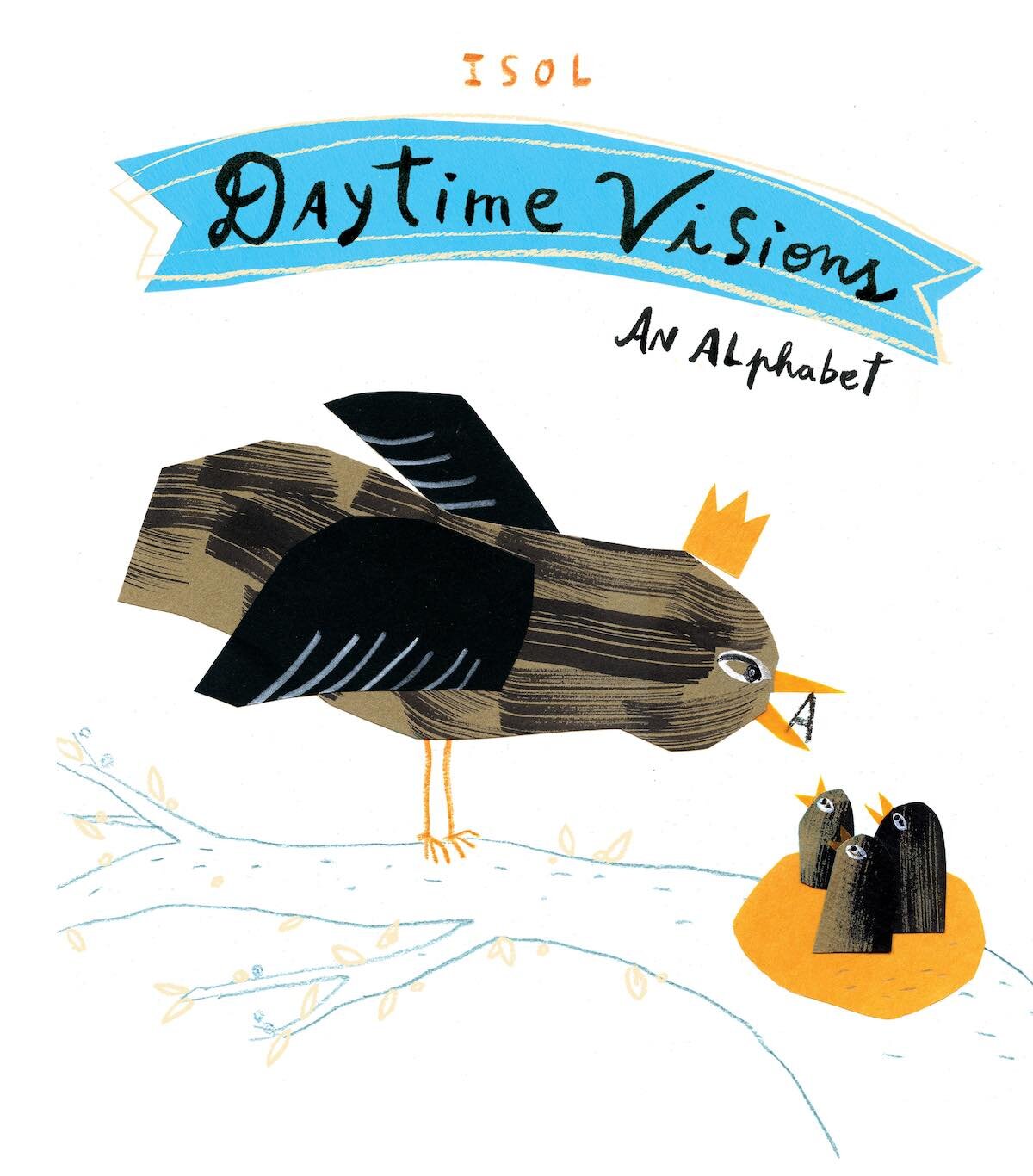

Cover of Daytime Visions: An Alphabet, Isol

Your path changed from teaching to writing and illustrating full time.

Well, I studied Fine Arts with the aim of becoming an artist, not a teacher. I like telling stories, drawing. I think teaching is a big responsibility. It is a job that needs a lot of creativity and wisdom, in order to help other people to find their own tools to express themselves. I sometimes do that kind of work, but I do not consider myself a teacher but rather an author instead, a storyteller that uses images and words to communicate.

Interior page from Daytime Visions: An Alphabet, Isol

When you share your books with children, what do you learn? Can you elaborate on your intent to leave your books open-ended, so readers can draw their own conclusions?

I try to learn all the time from everyone and everything. I have lots of questions. That's why I invent stories. I think that's one of the reasons why humans create things. I never know what kids will think about my books. I am always surprised they see so much, that they are so open. I like them very much because of that. I simply try to make a good book, and for me, a good book is one that keeps a certain sense of mystery and humor. Closed meanings usually lead to not such good literature. Even so, I do feel the urge to communicate. I don't want to make something that is not close to the reader, or maybe solemn or incomprehensible. I like to offer a good moment for a laugh, for thinking, for inspiration and definitely for new questions.

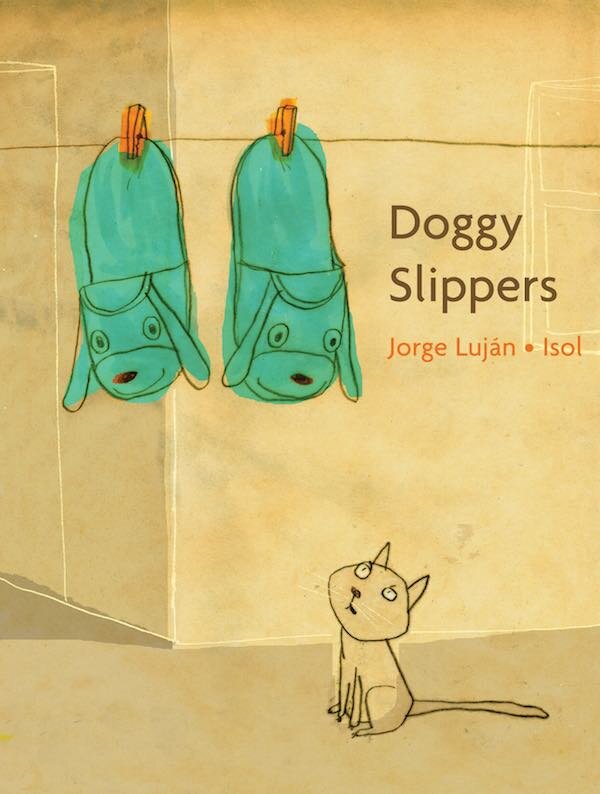

Cover of Doggy Slippers, by Jorge Luján, illustration by Isol

Interior spread from Doggy Slippers, by Jorge Luján, illustration by Isol

What do you think the judges from the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award meant when they said you expose the "absurdities of the adult world?"

My stories are usually told through some kind of child perspective that is not still shaped by our conventional beliefs or standards. I like to feel the strangeness of the world and to confront some ideas that we, as adults, use every day without thinking about them. I feel that's a nice way to be free and creative. I like to think like a kind of E.T. that has just arrived to Earth, just like a baby or an intelligent animal. I like to play with different perspectives to imagine different ways of feeling, seeing, understanding myself and others. I see a lot of absurd things in the way we live; I think that's quite interesting to think of. I think an ideal world and ideal people are not real, so I am not afraid of having screaming mothers or annoying kids in my books. I don't judge them, because I have things in common with them. We all are trying to have a clue about this life, and if we don't show these points of conflict our work becomes superficial.

You are skilled at seeing the world through a child's eyes. Do you think that comes from a clear memory of your childhood?

Really, I don't know. I used to think everyone has this memory about their childhood. For me, it is natural to travel in time to some scenes and remember clearly what I've felt. But I don't use the same situations I've lived when I write a story. I like being more fantastic or absurd. From the point I stand now I can see a situation with a new perspective. I have more humor now than I did as a child. I don't have certain fears that maybe I had. I don't try to please everyone anymore. So my invented children are wilder than I was.

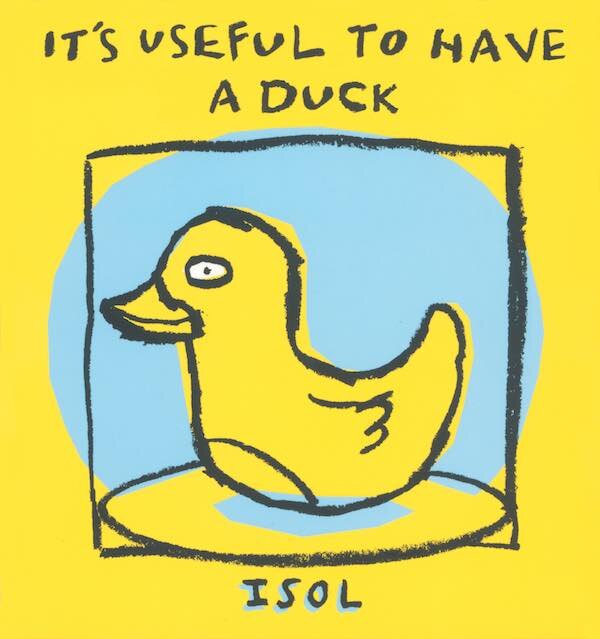

Cover of It's Useful to Have a Duck, Isol

Interior spread from It's Useful to Have a Duck, Isol

You enjoy exploring the boundaries of picture book creation: from It's Useful to Have a Duck that reads in two directions, literally from two points of view, to Nocturne: Dream Recipes with its use of fluorescent ink that reveals characters and details that can only be seen in the dark. How do you make these decisions?

Each book comes from a personal intuition or wish. It's Useful to Have a Duck came from a very simple idea when I was drawing a duck-boy scene and I thought: "Well, now, which one will tell the story?" I decided that each character could tell the same scene differently depending on their thinking about what was happening. These are the kind of things I love about picture book making; you can play a lot with images and words. The way in which you combine these two languages leads you to a huge range of meanings and possibilities. I design my books too. In this Duck book, the design is very important to tell the story — to make the joke about the two perspectives work, like an infinite book.

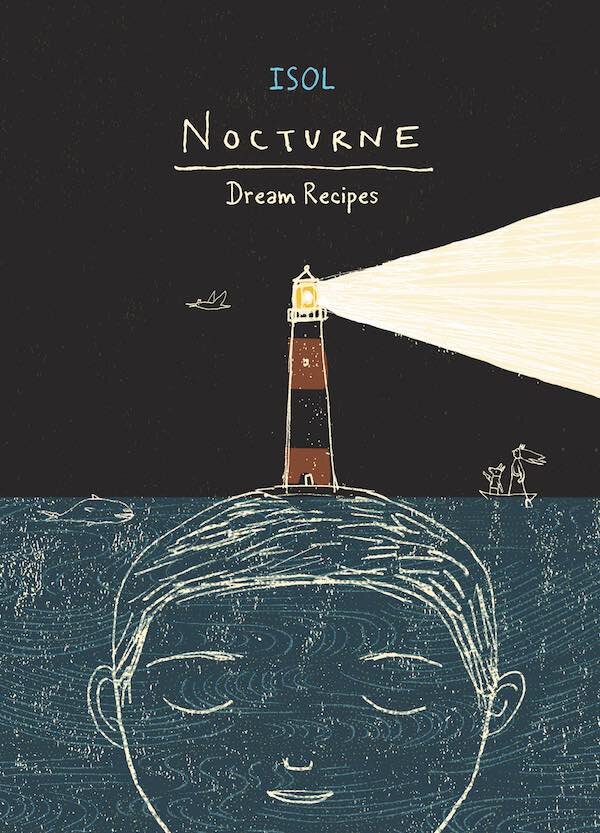

Cover of Nocturne: Dream Recipes, Isol

Interior spread from Nocturne: Dream Recipes, Isol

Regarding Nocturne, that is a book in which I wanted to try a special ink which glows in the dark. I thought it would be magical to have a hidden drawing on the page that appears only in the dark. Based on that need for darkness, it occurred to me the idea of a "dream recipes" book. So when I have the concept, it is nice to fill the empty spaces of the puzzle: style of drawing, text, sequence, shape of the book.

You typically use just a few Pantone colors, not CMYK process, in your illustrations. Do you find the simplicity of this type of palette a help to your creative process or an extra challenge?

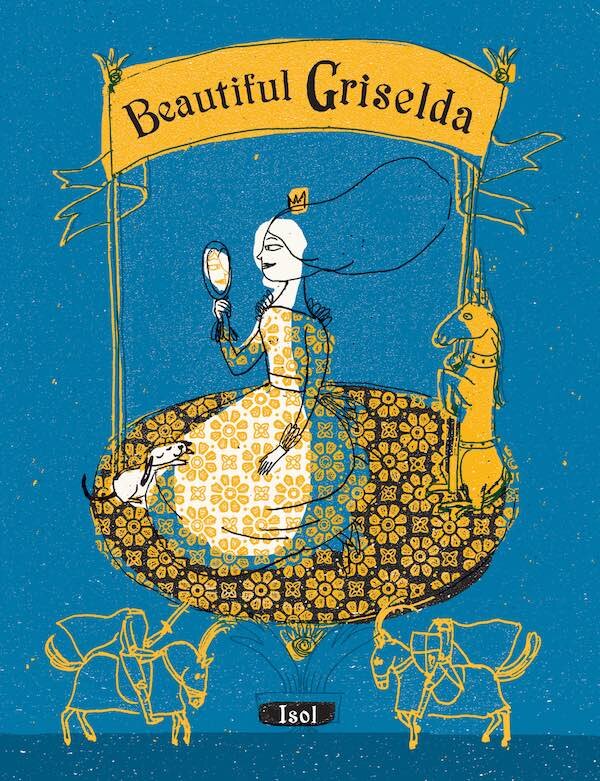

I use a simplified palette in many of my books just for aesthetic matters. I think it's more elegant. But I use CMYK usually. I used Pantone color just in It's Useful to Have a Duck and Beautiful Griselda in my search for better printing results. You're supposed to reach stronger colors that way. I suffer with printing, it seems so difficult to get the right color balance! In Beautiful Griselda I had to learn how to get a wide range of mixed colors with these separate inks. It was not easy but it was an exciting task. The same with Nocturne, in which I had to imagine the fifth ink, the glowing one, because I could not make a real test, only guess with the computer reference. I like learning new things, it is fun.

Cover of Beautiful Griselda, Isol

Interior spread from Beautiful Griselda, Isol

Do you always begin with pencil drawings in creating your illustrations? What other preliminary research or techniques do you use before you create the final art? One technique we read about was that you, a right-handed artist, sometimes use your left hand to keep your drawings loose.

I like lines with roughness. I use pencil, oil pastel, charcoal, dry brush. I use just a few lines, so I look for a very expressive and simple line in the same movements. I draw the same pictures many times trying to find something that surprises me. It's not that easy to run away from the paths you already know. I feel obliged to reach some strong point in each work, to bring some emotion. I use every tool that could help on that.

Isol’s studio

Do you keep a sketchbook?

I have lots of notebooks full of writing and little drawings. They are not those beautiful and polite sketchbooks I've seen by other illustrators, but they are very important to me. They keep the germ of most of my books, because I use them to find ideas when I am traveling or waiting for the doctor, for example. My mind seems more fluent when I don't have other things to do, just sitting, waiting, looking at people or through a window.

Sketches from Isol’s notebooks

Can you describe your use of the computer in developing your illustrations?

In Daytime Visions: An Alphabet, I used the computer just to design the pages. The drawings were entirely made by hand, because they were part of an exhibition in a gallery. In other books I use the computer to cut and clean up some sketches I then like to use as the final art. I use Photoshop to scan and mix papers for backgrounds and patterns, and to add color. I also need the computer to use Pantone colors in separate layers.

Interior page from Daytime Visions: An Alphabet, Isol

Many of your books have been translated into other languages. Does that affect how you write your stories?

It's true that I try to imagine if some games I do with words will work in other languages. For example, in Daytime Visions: An Alphabet, we had to rebuild the entire book, changing phrases and drawings because it was an alphabet, and it turned out to be a very creative exercise. I like to use common language in strange situations, so I choose carefully how to use the word in a simple but precise way. Sometimes, like in Beautiful Griselda, I've lost a final joke, but I work with the translator as much as I can to find a good option in those cases.

Interior page from Daytime Visions: An Alphabet, Isol

What is a favorite book from your childhood? Do you still own a copy?

I treasured a collection of illustrated books called Polidoro Tales. They were published in 1968 in very cheap editions but with very high quality of illustrations and texts. The drawings especially were for me a great inspiration. Very talented and free artists, a great project of the publishing house, Centro Editor de América Latina, which was banned later by the dictatorship we had from 1976 to 1983. I still have them and I've helped to relaunch a new edition of the collection in 2015 in Argentina, conceived for the Readers' Plan, aimed at being distributed in all schools in the country. I've felt it was like recovering a part of our art history.

Can you share a piece of advice from your early years that might be helpful to aspiring illustrators?

Try to tell something that you find really interesting. Read books. Nice drawings are not enough. Try to amuse yourself. Try to make your own projects and your own editions, even if they are homemade.

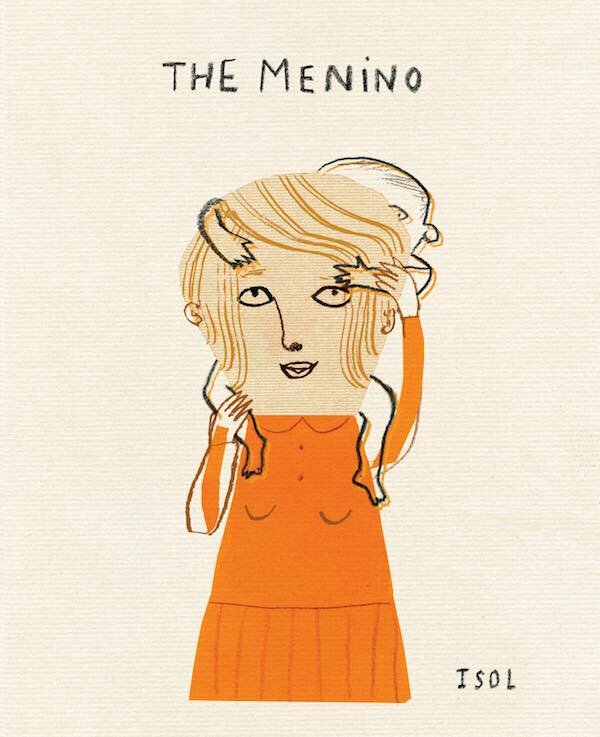

Cover of The Menino, Isol

Interior spread from The Menino, Isol

Are there any new projects you are working on that you could share with our readers?

Yes, I just finished a new book, it is not in English yet ;). It is called Impossible, a little story. It's another one about babies, parents and fulfilled wishes.

Thanks so much for sharing your work.

You are welcome!

For more on Isol:

Daytime Visions: An Alphabet, © 2016 by Isol, published in USA by Enchanted Lion Books.

All images are used with permission from Enchanted Lion Books.

Petit the Monster, © 2006 by Isol, translation © 2010 by Elisa Amado.

Doggy Slippers, © 2009 by Jorge Luján and Isol, translation © 2010 by Elisa Amado.

Beautiful Griselda, © 2011 by Isol, translation © 2011 by Elisa Amado.

Nocturne: Dream Recipes, © 2012 by Isol.

The Menino, © 2015 by Isol, translation © 2015 by Elisa Amado.

It's Useful to Have a Duck, © 2009 by Isol.

All the above listed books published in Canada and the USA by Groundwood Books Ltd.

Images reproduced with permission from Groundwood Books, Ltd.