An Interview with Adam Rex: Part 2

Adam Rex

We interviewed Adam Rex, children's book illustrator and author, as our launching post almost a year ago. A movie adaptation, HOME, of his middle grade novel, The True Meaning of Smekday, was just released by DreamWorks Animation. Here we share the rest of that first interview, as he discusses more about his process, and we have added an update on his upcoming and current picture book projects, including the third in his series by Neil Gaiman, Chu's Day at the Beach.

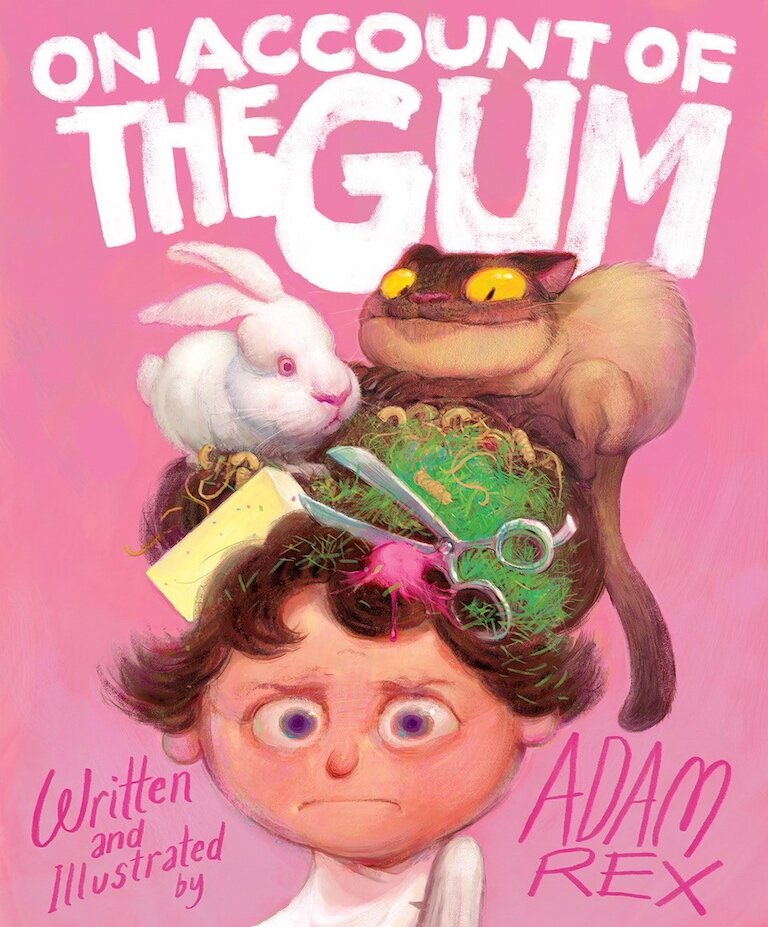

A Selection of Work

April 11, 2015

The last time we talked you were working a book with Christian Robinson.

Christian is doing work on the finished pieces right now. If you follow him on Instagram, you can see the posts of what he is working on. I think I'm lucky to be riding the wave of acclaim for Christian Robinson’s work. The Last Stop on Market Street and Josephine Baker have both picked up a lot of honors. It's beautiful work.

I have also sold another manuscript to Roaring Brook Press. Scott Campbell, of The Hug Machine, will be illustrating.

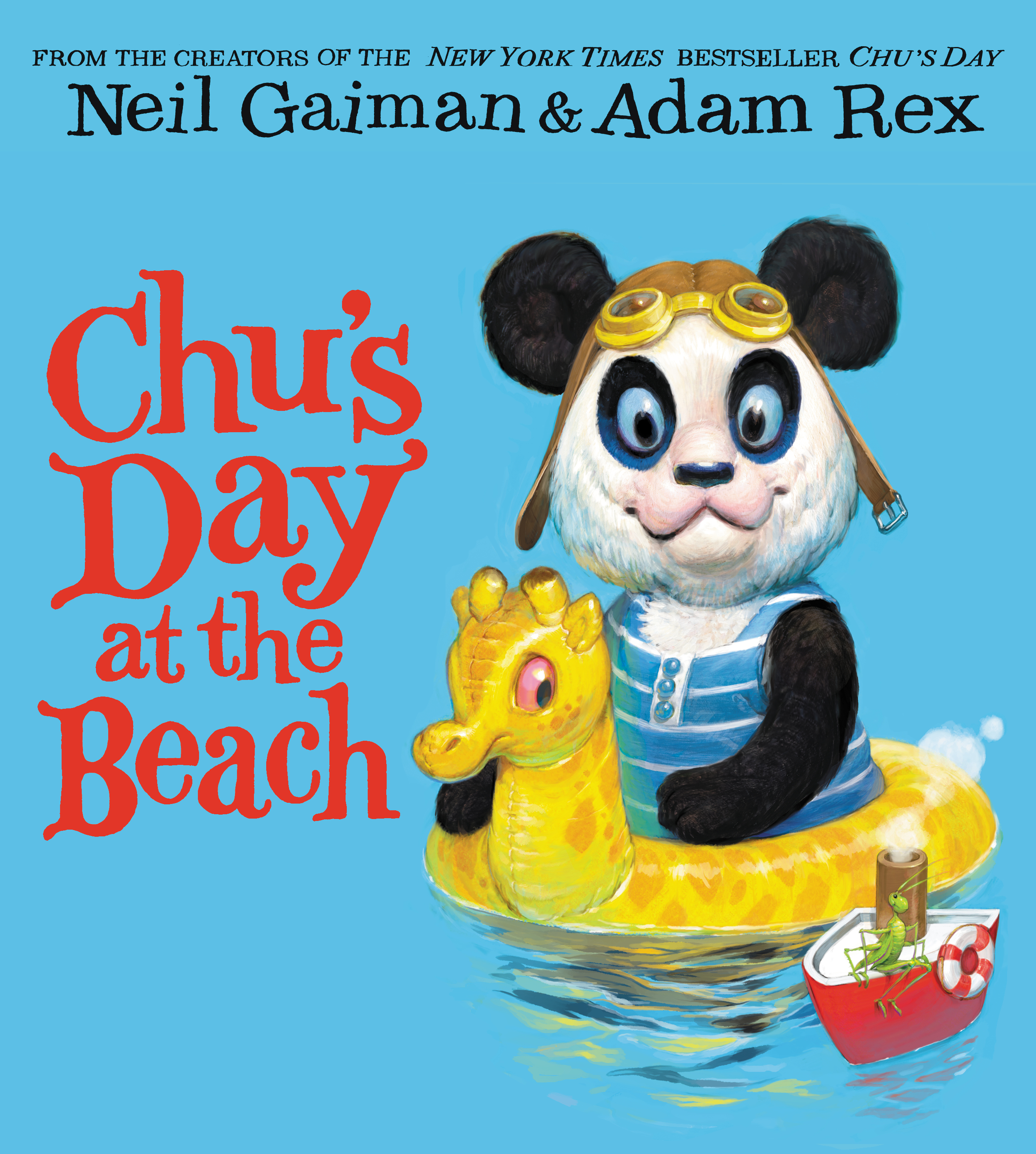

And I have a third book by Neil Gaiman that just came out, Chu’s Day at the Beach.

Chu's Day at the Beach, by Neil Gaiman, illustration by Adam Rex

What do you think of the latest one in this series?

It's a really fun premise. It is still building on the idea that was fostered in the first two books of this little panda with the big sneeze. It is a book that would be enriched if you already have some sort of relationship to his sneezing problem.

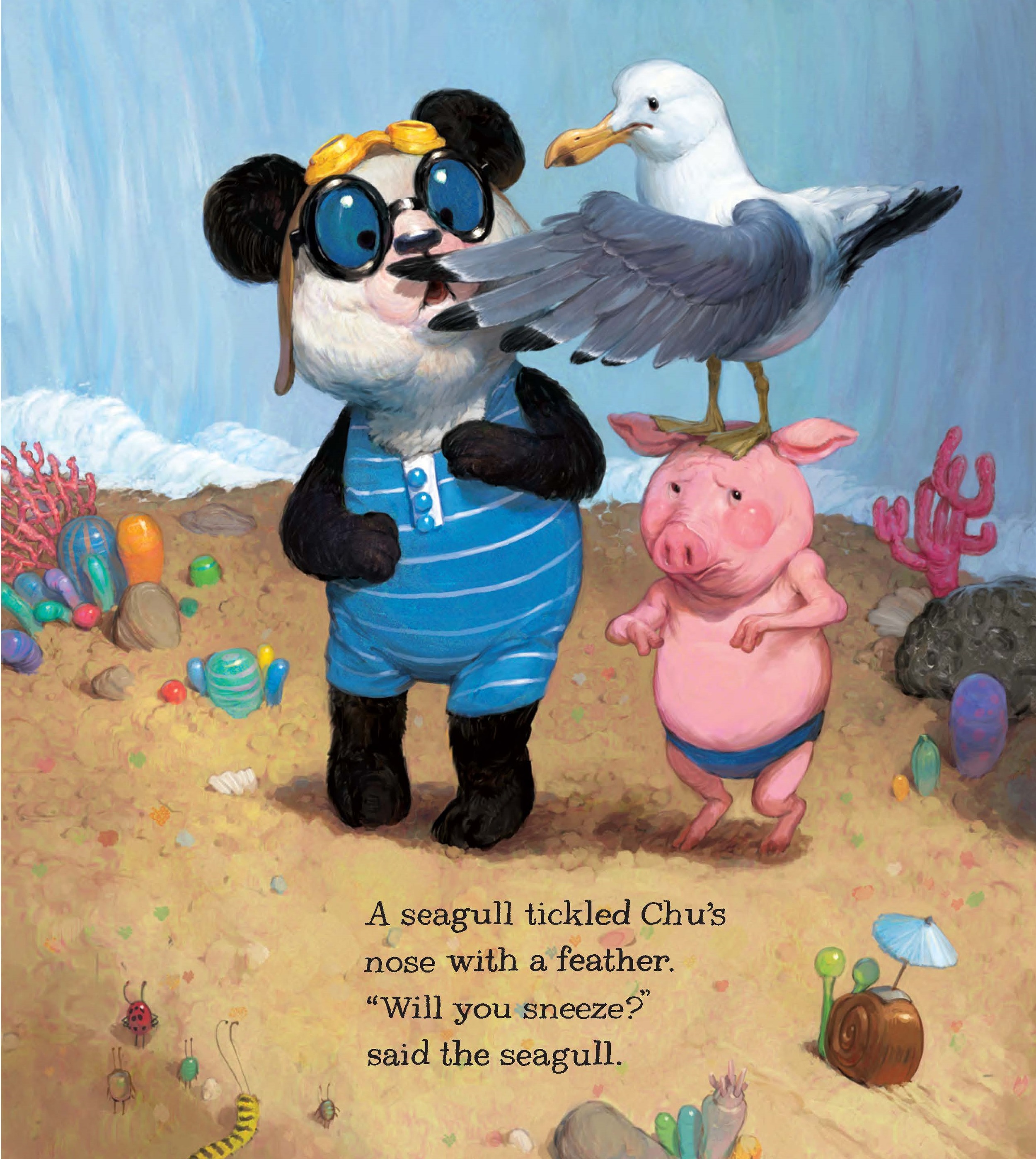

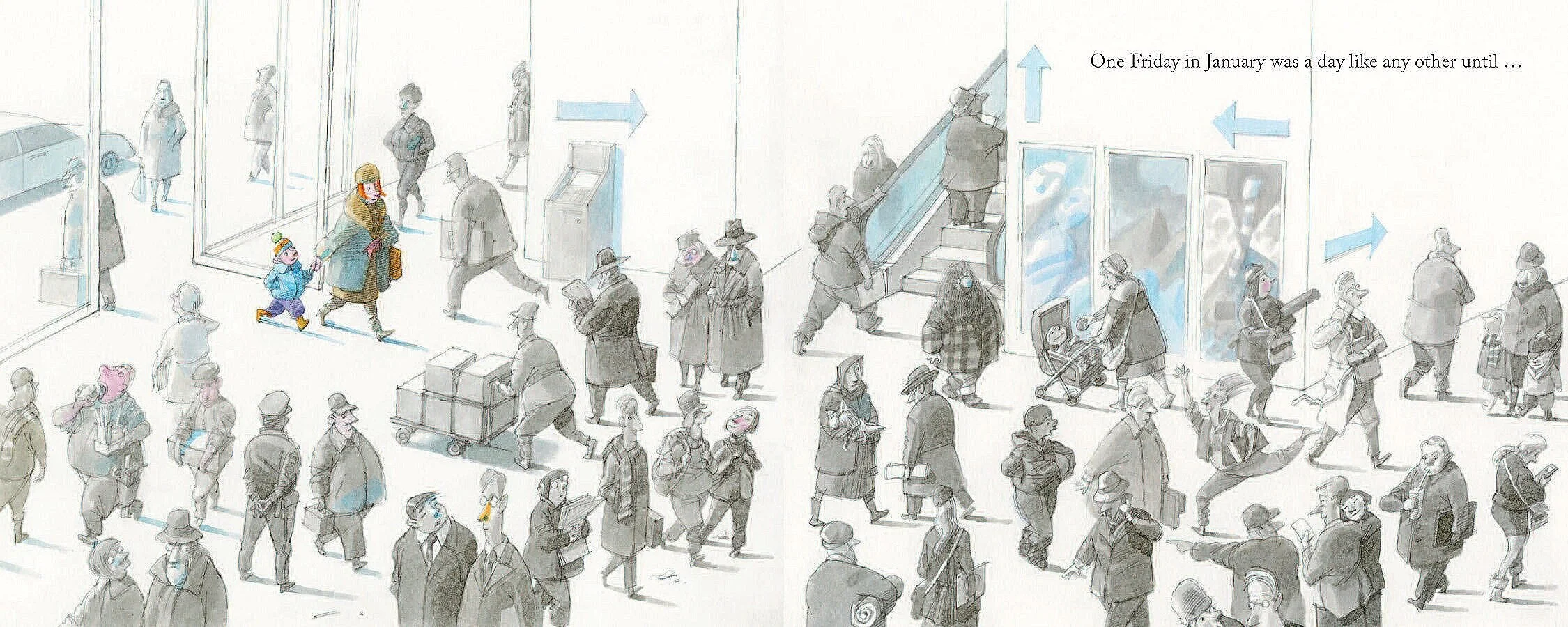

Interior spread from Chu's Day at the Beach, by Neil Gaiman, illustration by Adam Rex

So Chu sneezes and parts the ocean. Then the whole rest of the book is everybody trying to get him to sneeze again and put it back. But Chu can't sneeze and tries everything, fizzy drinks, tickling his nose with a feather. Nothing is working.

I'm really proud of how the illustrations turned out.

Interior page from Chu's Day at the Beach, by Neil Gaiman, illustration by Adam Rex

I am working on a picture book with Mac Barnett. It’s sort of a sequel to Chloe and the Lion, called How This Book Was Made. It is based loosely on a school presentation where he outlines and draws crude diagrams of the picture book making process. And of course it goes far askew from the actual picture book making process—it has pirates in it—but also hopefully imparts some idea of what the process is like. Especially the waiting part. It's probably the most waiting I've ever seen in a picture book, just whole pages of people waiting around and growing more beards and . . .

And is there conversation between the two of you as there is in Chloe and the Lion?

No, this is more of a realistic acknowledgment of the fact that we live in separate states and are not actually supposed to talk to one another. So it's about me being in Arizona and I’m being sent a manuscript. And he is waiting on comments from his mountain top peak in California and then to me finally getting around to working on his book.

Chloe and the Lion, by Mac Barnett, illustration by Adam Rex

With Chloe and the Lion, we admire the sense of shaking up what a picture book had to be, the idea that it must always be a story with pictures in a conventional sense. When you punched through that last wall separating you and Mac from the audience and had the interactions between the two of you and the little asides and the hand drawing, the humor, it opened up new possibilities.

Yes, it was kind of amazing to get that realized. I imagine Mac was playing that whole idea pretty close to the vest and wasn’t talking it up with friends. It seems so inevitable after you see it: oh yeah, of course. Why didn’t we think of this? And I should be clear: even though I have my own dialog in that book, he did write every word.

At Tucson Festival of Books over the years you have served on several panels on humor in picture books. You and Mac Barnett did a hilarious presentation for Chloe and the Lion.

Good. That was probably our practice schtick for presenting Chloe and the Lion to schools. Mac is great at off-the-cuff humor. But there's a reason why I am a humor writer rather than a standup comic. I'm a lot funnier if I have a little time to think about it.

There’s a post on Mac’s blog where he shows how he learned to draw a lion, in perfect imitation of your posts where you’ve showed your illustration process. He says, “First, as an illustrator, I have to do research,” and then after a day of this he draws a circle and then after another day or so of research he determines that a lion has a mane, so he adds a squiggly line.

That’s great. I think I have seen it. And he did do his own work for the book. How that worked out was that obviously I needed certain things to draw for those pages so I did my own messy drawings of the characters (I think I might have used my left hand), then I sent them to him and asked him to do his own version and he did several of each pose. Really if there were any true justice he should’ve gotten some kind of illustration credit, because everyone does ask that; they wonder if I did those drawings myself. I did my best to make mine look genuinely awkward and though it may sound strange to say or self aggrandizing, when you are a skilled artist it’s very difficult to make something look genuinely unskilled.

In publication design, a pet peeve has always been fake “kid writing”, for headlines on an article about a children’s topic, supposedly done with a crayon, with the backward “e” and every letter at a different rakish angle.

Oh right, the “lemonade stand” approach, where all kids don’t know which way their letters go. It’s a pet peeve of mine too, to the extent that whenever we’re watching a movie or a TV show and what’s ostensibly a child’s drawing of say, what the killer looked like in a crime procedural, my wife turns to me and says “Did a kid draw that?” “No, an intern did that.” I’m really impressed when they get it right. That’s either someone who actually knows how a kid draws or someone on the staff who brought in their kid.

Sometimes I am just in awe of kids’ drawings. I have one somewhere in my box of amazing things that kids have given me. A little girl drew the kind of car that a fish would have. It was a big round shape with wheels and a fish in the middle of it, colored blue, and it was a perfect little goldfish bowl car.

That’s the sort of thing that is very primitively drawn, but I could not improve on a line of this drawing, just an infinity sign with a tail. I wouldn’t change a single stroke of this drawing. It couldn’t have been made any better.

People assume that someone like me, that is known for a painterly, semi-realistic illustration, that I’m not going to appreciate the little budding Mattises of the world. I completely do. I envy them; I envy the ability to make something that potent without having to be worried that “I haven’t proven once again, that I can draw a really realistic looking fish, so I guess I’d better erase this.”

It happens early with children when they clutch up and . . .

Oh, absolutely, I think that’s why most of them stop drawing.

They become such harsh critics of their work. Younger, they draw freely. But soon, someone says "I love the way you draw this” and they respond “No, that doesn’t look anything like a dog.” and they wad it up.

Yes, I would like to have a better understanding of why kids stop drawing at whatever age they stop, which I have some sense is around ten or twelve or fourteen. I think there’s sort of a winnowing at a certain age where, you decide that you should only be allowed to continue doing whatever you are good at. “I’m not the best artist in the class, so what am I still drawing for? Why would I want to open myself up to comparison to that one kid in the class that everyone comes up to and asks “Can you draw me this?” Lucky for me, I was that kid, and I wasn’t going to stop doing anything that was universally accepted to make me special. Especially after I found out that being one of the smart kids wasn’t valued anymore, so I clung to being the kid who could draw, my entire life.

At the same time, I look back and I wish I had been the second best kid in the class. Looking now at sensational artists who are just in their teens. I think: wow, I could have been so much better back then, but there was no one pushing me. Certainly my teachers weren’t. They were usually just vaguely annoyed that I was always drawing in the margins and on the back of my assignments. My parents never gave me anything but support, but they also didn’t say “Why don’t you try this or that? Why don’t we enroll you in more classes?" because even though they never told me that I shouldn’t be drawing, they were also terrified at the prospect of a son who thought he was going to be an artist. I didn’t know that until I was an adult, because I have a good mom and dad.

I meet a lot of adults who almost insist that art technique can’t be learned, that it is something you are born with or not. Which, as an artist, is easy to find offensive. Yes, maybe I was born with a slight edge, where at five years old, people thought, “This kid is a little artist.” And that, plus thirty five years of work, got me where I am now.

You can learn to be a better artist. I sometimes wonder if there isn’t just an insistence that no, you can’t learn to do those things, because if you could learn, then each person would have to take responsibility for not doing those things.

Right, no excuses left.

I used to wonder if everyone but me was pulled aside, maybe on a day when I had the flu, and told them that this is what you say when you meet an artist. ”I can’t even draw a straight line” or, “I can’t even draw a stick figure.” The true answers to which are, respectively, “No, I can’t either, that’s what rulers are for and yes, you can.”

You have said that people easily accept that you can illustrate a hippopotamus in full cover and three dimensions, but are shocked beyond measure that you can draw a letter A by hand.

Yeah, there is this dichotomy between type and pure illustration where they are just amazed that you can make a serif A look like a serif A. It’s all just drawing. But it is interesting. I wonder how many graphic designers have lost the ability to draw type. They rely so much on an enormous type catalog that they don’t have to sketch something.

Was it an adjustment to begin creating art digitally compared to using pencils and brushes?

Not really. It took me about a day to get used to the fact that I was actually drawing in my lap, but staring straight ahead at a monitor rather than looking at whatever my hand was doing. I’ve met a lot of people who never get used to it, so it seems to be a certain kind of brain chemistry that either allows you to work this way or not. The more recent versions of these tablets are essentially a screen that you’re holding and drawing directly onto. In a weird sense, when I first heard about the screen-in tablet, I had the dumbest reaction. I thought well, why would you want the screen where you are drawing because then your hand would be blocking the thing that you’re drawing. Then I realized that, oh right, that’s exactly like every traditional drawing that I’ve ever done in my entire life. But I was so used to this draw-down-here, look-up-there mentality . . .

What about color? Is it the tablet only for the initial line drawing?

No, I paint in Photoshop on the tablet. I try to make it so the digital painting experience is as similar to oil painting as possible. Such that I hope that with some of my paintings people aren’t even aware that they are digital.

There has been this long standing tradition in children’s picture books where illustrations have been in watercolor.

Yes, it was just a restriction of the printing process for a while. When we think of the books from our childhood, we think of books that were just black line with maybe one or two process colors, rather than a full color printing process. They didn’t have printing presses that were great at printing color halftones, so you didn’t see these lush, painterly picture books. I think traditionally people used watercolor or acrylic in illustration because oil is not the smartest medium to use. It takes longer to dry for one thing. But it’s what I’m best at, so . . .

It seems you’ve made a successful transition from oils to the digital painting you do on the tablet.

And I still do both, digital and oils. The first Neil Gaiman book, Chu’s Day, is actually all oils, traditionally painted and then another book of mine, Billy Twitters and His Blue Whale Problem is entirely digitally painted. That was my first book that was all digital.

So you’re able to get closer and closer to your painting style.

Yes, I think I’ve gotten better at simulating what I want. I’m a little more accomplished now than on Billy Twitters. There was a learning curve.

Do you carry a journal for idea gathering, random notes, sketching or writing? Is that a habit for you?

I do always have one or two sketchbooks going. More than anything though, it’s a place where I am starting my own illustration projects. I’m sorry to say that I rarely sit in cafes and draw for fun like I used to. So I don’t have sketchbooks filled with flights of fancy that might turn into something. It’s more likely to be working sketches for page 29.

Adam's "first ever drawing of a Boov" from a sketchbook

With writing, that’s happening more on my laptop than in my sketchbook. I’ll get something in my head and I’ll stop what I’m doing, open up a new page and type for a while, save it, and hope I can find it later. I‘m worried that if it’s in my sketchbook, I’ll never find it again, that I won’t have a reason to go back through that particular sketchbook.

You use humor frequently and effectively in your work.

It’s commonly understood that with the reluctant reader (i.e., boys) you rope most of them in with humor first.

Books can be deadly serious and terribly sad at times and also hilarious and the humor doesn’t undercut things, it actually tends to amplify it. If I just made you laugh, then when I make you cry, you’re going to cry because you’re already in an emotional state. That’s what I try for in my work: to be able to be both funny and serious and sad and exuberant all at the same time.

Boov and Tip from HOME, DreamWorks Animation

Your book The True Meaning of Smekday was just adapted and released as the movie HOME by DreamWorks Animation. What was it like to attend the screening?

What was really fun about the screening was that it was for the employees, so it was like a high school graduation. The scroll would bring up the marketing department and there’d be a smattering of boos and cheers from the seven people in the marketing department and then it would be casting and somebody seated next to me would go “Woo!”.

But I spent the entire movie waiting to see if they had used any of my jokes. I think I was a little distracted.

They used a fair bit from the book but they also wrote their own material and it goes off in its own direction. Some months back they asked me to have a look at the script and see if I would be willing to punch it up with extra jokes here and there. So I wrote them a bunch of material. And it was that material that I was waiting for the entire ninety minutes of the movie. So while I enjoyed the movie very much, a lot of it was me going, ”Okay, they didn't use that joke. Not that joke either apparently. But in the next part? No, not there either."

So now that I know all that, and can't be disappointed again, I can relax and enjoy it at the premiere.

It was very nice at the end of the movie watching the credits, to see film by Tim Johnson and then the fourth or fifth title card was “Based on the book by Adam Rex, The True Meaning of Smekday.” So that was still kind of thrilling to see that.

So you met the screenwriters?

Yes and I liked them very much. One of them shared a great line, “We changed the plot but not the story.” And that made sense to me. I fully expect to get emails from irate readers. I understand about liking something and wanting it to be exactly that way on the screen.

But I don’t think you can ruin a book with a movie. Not a word of my book will ever be changed by the movie. Movies should be entitled to be their own thing, to tell their own story.

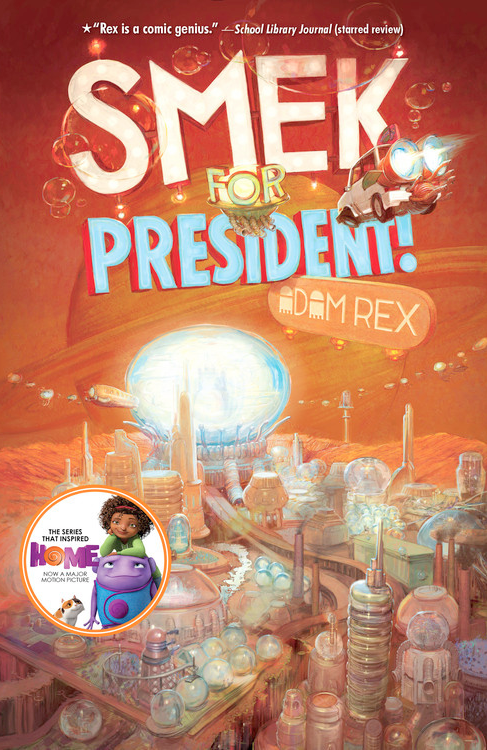

You have a second middle grade novel that just came out, Smek for President!

Yes, it’s the second in, as they call it, the Smek Smeries.

I will always do picture books as well. All that will ever happen is I will get an idea for something and the idea is going to be obviously a novel or a picture book. It's not really a matter of thinking, “Well, I should be thinking up a picture book right now. I'll spend a couple days coming up with picture books.” If I'm lucky I come up with an idea and that idea is obviously not for a four hundred page novel or obviously not for a thirty-two page picture book.

And it's not always all obvious. The True Meaning of Smekday started out as a picture book just because I had never written a novel and I wasn't sure I could it. So I did it up in the only way I knew how, which was as a picture book and then put it away for a while. Then I slapped my head and saw that it was a novel, started writing it as such and not telling anybody except my wife that I was working on it until I had 15,000 words. Only then did I start showing it to people, including my agent, Steven Malk, who sold it on that basis.

Again, we thank you for the time you have spent sharing your work.

For more on Adam Rex:

Interview with Adam Rex & Mac Barnett

All images used with permission from Adam Rex.